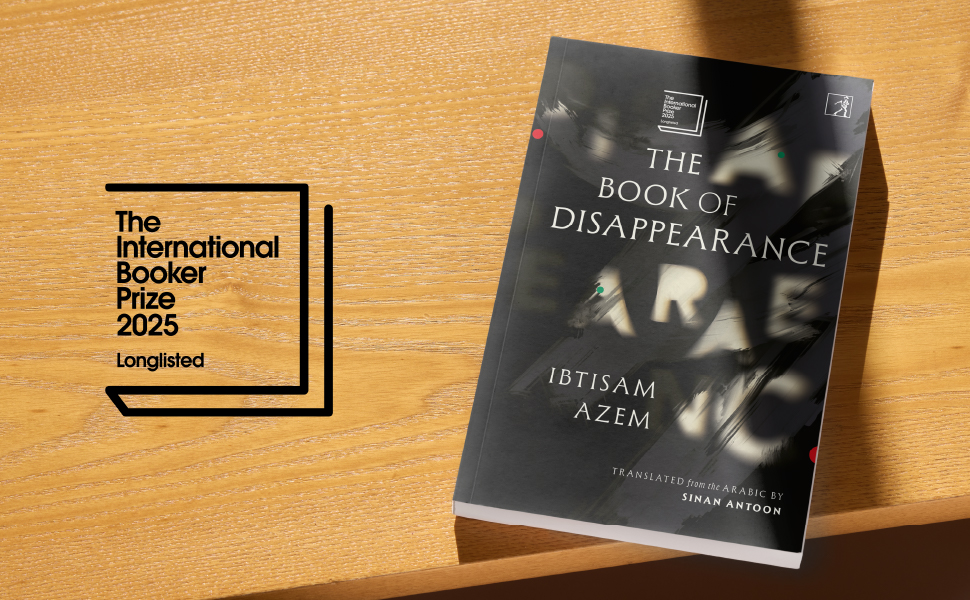

The Book of Disappearance by Ibtisam Azem, translated into English by Sinan Antoon and published on 8 April 2025, is a striking work of speculative fiction that imagines the sudden vanishing of all Palestinians from Israel and the occupied territories. Through this bold premise, the novel forces readers to confront questions of identity, memory, and erasure. At its heart are two characters: Alaa, who inherits his grandmother’s painful memories of displacement during the Nakba, and Ariel, a liberal Zionist journalist who wakes up one morning to find his Palestinian neighbours gone. Their contrasting perspectives set the stage for a powerful exploration of history and its silences. Azem reminds us that “history is stories and stories have histories,” emphasizing that the past is never neutral and must be remembered.

Blending the past with the present, The Book of Disappearance unfolds in the cities of Jaffa and Tel Aviv, where everyday life continues even as absence reshapes its rhythm. Alaa’s notebook captures the fading scents, forgotten songs, and buried grief of a people denied their history, while Ariel’s search for answers reveals the tensions within Israeli society itself. The narrative also shows the deep attachment people have to their homeland, as reflected in the line, “She preferred to die in Jaffa than to leave it,” highlighting that for some, staying in one’s place of origin, even in danger, carries profound significance. Between café patrons, radio commentators, and ordinary citizens, the novel paints a haunting picture of what is remembered, what is forgotten, and what is deliberately erased. The interplay of voices makes this novel both intimate and political, reflecting the deep fissures of the Palestinian question.

Praised for its spare yet lyrical prose, The Book of Disappearance is more than just a story of disappearance; it is a meditation on belonging and loss. Azem’s narrative, enriched by Antoon’s sensitive translation, challenges readers to think differently about identity and survival in a contested land. By weaving together memory, history, and imagination, the novel becomes a powerful reminder of how literature can preserve what political systems try to erase. Its themes of displacement, resilience, and cultural memory give the book enduring relevance in today’s world.

Finally, writing The Book of Disappearance is a way of leaving testimony. Alaa’s diary is not just personal reflection but an act of resistance and a record of stories that might otherwise be lost. Writing becomes the only tool to fight erasure, giving voice to the disappeared and confronting the silence left behind.

Read Also: Forest of Noise | Mosab Abu Toha | Poetry of Gaza

Book Details and Availability

The Book of Disappearance by Ibtisam Azem, translated into English by Sinan Antoon, will be released on 8 April 2025 by Simon and Schuster. Originally written in Arabic, the novel is now available to English readers in a 240-page paperback edition priced at ₹364, as well as in a Kindle edition for ₹309. The book is known for its spare yet powerful writing and its sharp mix of different perspectives. It gives readers an unforgettable look into present-day Palestine, exploring both the memory of loss and the painful reality of forgetting.

Read Also: James | Percival Everett | Book Review

About the Author and Translator of The Book of Disappearance

Ibtisam Azem is a Palestinian novelist, short story writer, and journalist who lives in New York. She was born in Taybeh, near Jaffa, a place deeply connected to her family’s history of displacement during the Nakba of 1948. Azem studied at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem before continuing her education in Germany, where she received a master’s degree in Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies with minors in German and English literature. She later earned another master’s degree in Social Work from New York University. Azem is the author of two acclaimed Arabic novels, The Sleep Thief (2011) and The Book of Disappearance (2014). Her work has been translated into English, German, and Italian, and her stories and essays have appeared in respected literary journals around the world. Her upcoming short story collection City of Strangers is expected in 2025.

Sinan Antoon, the translator of The Book of Disappearance, is an Iraqi poet, novelist, and academic. Born in Baghdad, he later studied in Iraq, the United States, and Europe, completing advanced degrees in Arabic literature. He has published several novels and poetry collections, and his work as a translator has introduced Arabic literature to a wide international readership. His translation of Mahmoud Darwish’s In the Presence of Absence won the American Literary Translators’ Award in 2012. Antoon teaches Arabic literature at New York University and continues to write, translate, and publish widely. His English translation of Azem’s novel received international recognition and was longlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2025.

Read Also: Hunchback | Saou Ichikawa | Book Review

Thematic Analysis of The Book of Disappearance

How would a society look if an entire people suddenly vanished overnight? What traces of their presence would linger, and how would those left behind respond to the silence? These haunting questions drive Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance, where Alaa carries his grandmother’s memories of exile from Jaffa after the Nakba, while Ariel, a liberal Zionist and his neighbour, questions Israel’s military rule in the West Bank and Gaza yet remains committed to the state itself. One morning, Ariel wakes to the shocking reality that every Palestinian has mysteriously vanished, forcing him to confront a world stripped of their presence. Through their intertwined perspectives, the novel unfolds its themes of memory, erasure, belonging, and the fragile line between history and forgetting.

- Memory as Inheritance: In The Book of Disappearance, memory is a living thread that passes from one generation to the next and shapes identity and grief. Alaa carries his grandmother’s stories as a duty and as a wound, showing how remembrance becomes a form of survival. The novel asks what remains when official histories refuse to see what people remember in their bones. “We inherit memory the way we inherit the color of our eyes and skin. We inherit the sound of laughter just as we inherit the sound of tears. Your memory pains me.”

- The Fog of Remembering: The Book of Disappearance shows that memory is not a fixed archive but something that shifts with time and pain. The past appears and disappears like mist, and yet it still guides how people see their city, their family, and their loss. This tension gives the book its quiet power. “But memory is dense fog that spreads or clears as one gets older.”

- Presence Through Absence: The sudden vanishing makes absence feel louder than presence in The Book of Disappearance. Daily routines collapse and relationships are exposed, and what remains is loneliness that has no easy cure. The book shows how erasure breaks both public life and private bonds. “Survivors are lonely”.

- A City Wears Another City: Jaffa is layered with older Jaffa, and The Book of Disappearance reveals a city that contains another city beneath it. Streets and names feel familiar yet changed, as if the past has been expelled while still haunting the present. This double vision becomes a map of grief. “You used to say that you would walk in the morning, but couldn’t recognize the city or the streets. As if they, too, were expelled along with the people who were forced to leave”.

- Shortened Lives and the Politics of Forgetting: Lives are cut and stories are edited by power, and The Book of Disappearance shows how this truncation breeds confusion and pain. The mind tries to store what is too hard to face, yet the storage itself hurts. This is how denial deepens loss. “What we live is truncated… So we store memory in a black box inside our heads and hearts, but it pains us and gnaws from within. And we rust, day after day.”

- Normalizing War: War becomes a background noise that people learn to ignore in The Book of Disappearance. The novel refuses that numbness by making absence impossible to overlook and by insisting that every silence has a cost. It turns routine into a wakeup call. “There are so many wars around us we’ve gotten used to them.”

- Exile, Staying, and the Pain of Choice: Displacement is not a simple move from one place to another in The Book of Disappearance. The book shows how both staying and leaving can feel like a kind of death, and how home can turn into a wound that never closes. This truth sits at the heart of the characters. “No one leaves their country just like that. Leaving was like suicide, and staying was suicide too.”

- Haunted Ground: Place itself remembers, and The Book of Disappearance makes the land feel heavy with what happened there. Walking becomes an act of witness, because the ground holds stories that official maps do not show. These haunting rejects the idea that history is over. “When I walk in Palestine I feel that I am walking on corpses.”

- Media Frames and Wishful Headlines: The public story is not neutral in The Book of Disappearance. Headlines try to turn loss into relief and absence into a solution, showing how language can hide violence while pretending to explain it. The book exposes this mask. “News headers like: Have Our Problems Disappeared Forever?” “Have All Our Problems Been Solved, Once and for All?”

- Us and Them: Binary thinking drives policy and daily choices in The Book of Disappearance, and it feeds a cycle where empathy shrinks and fear grows. The novel shows how this logic flattens people into problems to be managed. It is a warning about what division makes possible. “It’s either us or them.”

- Rights, Voice, and Ongoing Resistance: Even when bodies vanish, the claim to dignity does not in The Book of Disappearance. The novel insists that demanding rights is itself a form of presence that resists erasure and keeps history alive. The act of insisting becomes the pulse of the book. “Rights are never lost as long as one demands them.”

- Doubt, Faith, and the Problem of Evil: Pain raises hard questions about meaning in The Book of Disappearance. The characters wrestle with belief and disbelief as they face loss and injustice, and the novel lets those questions stand without easy answers. That honesty deepens its moral force. “Had there been a God, this wouldn’t have happened.”

- Language as Escalation: Public speech hardens when fear rises in The Book of Disappearance. Shouting replaces listening, and debate turns into noise that blocks understanding. The novel shows how language can either heal or harm. “I think that’s the only language they understand. Yelling.”

- Naming the Central Shock: The novel circles the mystery at its core and treats it like a marker in time that people use to sort fear, hope, and policy. In The Book of Disappearance, that naming does not solve the mystery, but it shows how societies try to control what they cannot explain. “The Disappearance Event”

- Love, Longing, and the Pain of Staying Human: Beneath politics the book holds a tender ache for people and places, and The Book of Disappearance shows how longing keeps memory alive even when it hurts. Love does not erase loss, but it keeps a door open to the past. “Longing for you is like holding a rose of thorns! Longing is thorns.”

- Storytelling as Resistance: The Book of Disappearance also presents storytelling as a powerful form of resistance. Alaa’s diary entries, filled with his grandmother’s memories and his own reflections, become a testimony against erasure. By writing, he preserves the voices of those who can no longer speak. The novel shows that while people may be made to disappear physically, their stories remain as a reminder of injustice and a call for recognition.

- Power, Erasure, and Justice: Finally, The Book of Disappearance raises hard questions about power and justice. The disappearance is never explained, leaving readers to confront what Israeli society does with this “miracle.” The novel reveals how quickly absence is exploited and empty homes are taken, laws are rewritten, and new divisions emerge. This theme highlights how systems of power thrive on erasure, and how the struggle for justice continues even when a people are no longer there to fight openly.

Quotes from The Book of Disappearance

Read Also: Eurotrash | Christian Kracht | Book Review

- “I write to remember and to remind, so memories are not erased. Memory is my last lifeline.”

This line shows how writing is not only a creative act but also a form of survival. For the narrator, memory keeps identity alive in the face of erasure. Writing becomes a weapon against forgetting, making memory a lifeline that connects the past with the present.

- “An illusion is enough to live the lie that later becomes the truth.”

Here Azem warns about how repeated illusions or false stories can gradually become accepted as truth. It reflects how history can be manipulated, and how dangerous it is when lies are allowed to replace reality.

- “It was a coincidence that her family survived.”

This simple but heavy line highlights the randomness of survival in times of war and displacement. It suggests that survival was not always due to strength or planning, but often just chance.

- “Perhaps I am writing out of fear. Against forgetfulness. I write to remember, and to remind, so memories are not erased. Memory is my last lifeline.”

This repetition underlines how fear of forgetting pushes the narrator to write. Writing here is both a personal therapy and a collective duty to keep history alive, especially when voices risk being silenced.

- “Sometimes I feel so sad I cannot cry.”

This line captures deep grief that goes beyond tears. It shows how sorrow can be so heavy that it numbs the ability to express it, leaving silence in place of crying.

- “But my father was always busy with work. Do you know I think it’s because I didn’t know him well that most of my memories with him are beautiful?”

This bittersweet memory reflects on absence. Because the father was distant, the few memories that remain are mostly idealized. It shows how distance and longing can shape memory into something more beautiful than it really was.

- “I neither hate the Arabs nor love them. They don’t mean much to me. I just want them to leave us alone. But I doubt that that’s possible.”

This voice of an Israeli character shows indifference mixed with exhaustion. It reflects a desire for normal life without conflict but also the recognition that peace may not be possible in the current situation.

- “Were it not for the persistent pinpricks of conscience, things would be fine.”

This line shows how guilt and conscience disturb daily life. Without those reminders, one might live comfortably, but moral awareness keeps surfacing, making it impossible to ignore what has happened.

- “If God wanted to be merciful to him, he would’ve done so while he was still alive.”

This reflects a harsh view of suffering and divine mercy. It questions the value of mercy after death, suggesting that real compassion is needed in life, not after.

- “Just like Nasser said. ‘What’s taken by force can only be taken back by force.’”

This line recalls the words of Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, pointing to resistance as the only path to regain what was lost. It reflects the politics of struggle and the belief that oppression can only be undone through equal strength.

- “It is no longer possible to live in a country where the desire to eliminate the other has reached the level of genocide.”

This powerful line addresses the extreme point of conflict where coexistence seems impossible. It shows the fear and despair when violence and hatred are so strong that they threaten the very survival of a people.

Read Also: The Emperor of Gladness | Ocean Vuong | Book Review

Why You Should Read The Book of Disappearance

“War was a big word when I was young. But I grew bigger and it grew smaller. There are so many wars around us we have gotten used to them.”

Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance begins with a haunting question: what if, one day, all Palestinians vanished without a trace? Through this unsettling premise, the novel asks readers to confront silence, absence, and the weight of history.

The story unfolds in two voices. On one side, Ariel, a Jewish Israeli and a liberal Zionist search for his missing Palestinian neighbours and friends, carrying the fears and uncertainties of those left behind. On the other side lies a red notebook he finds on his friend Alaa’s table. In it, Alaa writes letters to his late grandmother, who survived the Nakba and carried the pain of becoming a refugee in her own homeland. These two perspectives bring together the themes of memory, loss, and erasure in powerful and moving ways.

Azem’s language is poetic but direct, blending personal reflection with political reality. The writing style moves gently between the intimate and the collective. Azem’s writing flows between fear and longing, between personal grief and collective memory. Her language is lyrical yet sharp, forcing readers to see how absence itself can become louder than presence.

This novel deserves to be read because it does not simply tell a story instead it confronts us with history, responsibility, and the fragile bond between remembrance and forgetting. I t forces us to think about how societies remember, how they forget, what happens when a whole people are erased not only from daily life but also from history. Urgent, powerful, and deeply humane, it leaves us with questions that linger long after the last page.

“When I walk in Palestine, I feel that I am walking on corpses. What are we going to do with all this sorrow? How can we start anew? What will we do with Palestine?” This question echoes beyond the pages, leaving readers to carry it with them long after the book ends.

Final Thoughts

Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance is more than just a story and it is a reminder of how memory, history, and identity shape the lives of both Palestinians and Israelis. The novel painfully observes, “It is no longer possible to believe in tolerance, or dialogue, because there is no one left to have a dialogue with,” a line that captures the devastating silence left in the wake of disappearance. By showing what happens when an entire people vanish, the book compels us to face questions of absence, loss, and the responsibility of remembering. Written in poetic yet powerful language, it leaves readers with a deep sense of sorrow but also with the awareness that silence and forgetting can be as destructive as war. This is a book that lingers long after the last page, urging us not to turn away from pain but to understand its meaning.

Read Also: Dream Count | Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie | Book Review